I've been modding Cyberpunk 2077 for over two years. With about 3M+ downloads across all of my mods and in all that time, I'd never touched quests.

There's a running joke in the modding community: writing quests is considered harder than writing scripts - which is a little absurd when you think about it. The whole point of visual node-based systems is to make quest design accessible to non-programmers. Quest graphs do get complex and sure, there are a lot of programming-adjacent concepts like logical gates and state management but they're a lot more intuitive than learning programming syntax from scratch - which is what most modders end up (most often not successfully) trying to do.

Most quest designers at game studios aren't typically coders, yet here we were, a community of modders who could write complex scripts, finding quests intimidating. When I first tried making quests early in my modding journey, I gave up within days. The tools to edit quests existed in Wolvenkit, but the docmentation around quests was non-existent so the learning curve was steeper than usual.

The catalyst

I got pulled back into quests after I finally got around to watching Neon Genesis Evangelion. The series left me with ideas bouncing around my head for weeks - themes about consciousness, identity, and choice that felt like a perfect complement to Night City. I had this vision for a quest involving the Blackwall, a mysterious BD, and choices about what we'd live or die for.

This time around, I had more context. Through mods like Nitrous and Gonkle, I'd been indirectly touching quest systems - like manipulating journal entries via scripts. In Nitrous, El Capitan messages you and charges you for installing NOS in your vehicles, all done through quest resource manipulation. And in some other mods, like Generous V - I poked around quests a lot on the side so I understood pieces of the puzzle. Maybe this time would be different.

Learning from the masters

The best way to learn quest design is to study existing quests. Cyberpunk's biggest quests and scenes often have over a thousand nodes (easy) but naturally for learning I needed something simple and self-contained. I started with mq049 - the Edgerunners easter egg quest.

It's simple: player finds a BD on a corner, watches a braindance, then proceeds to gets some journal messages. Perfect for learning.

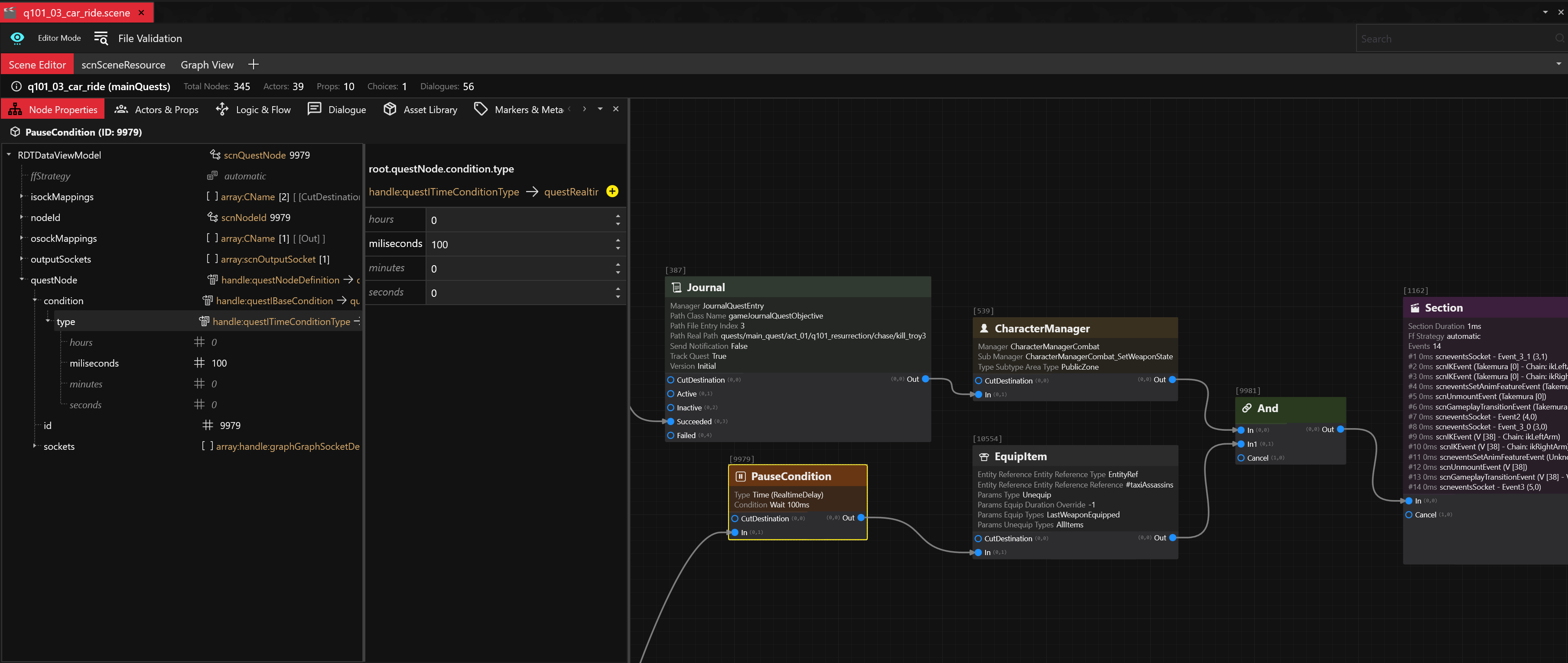

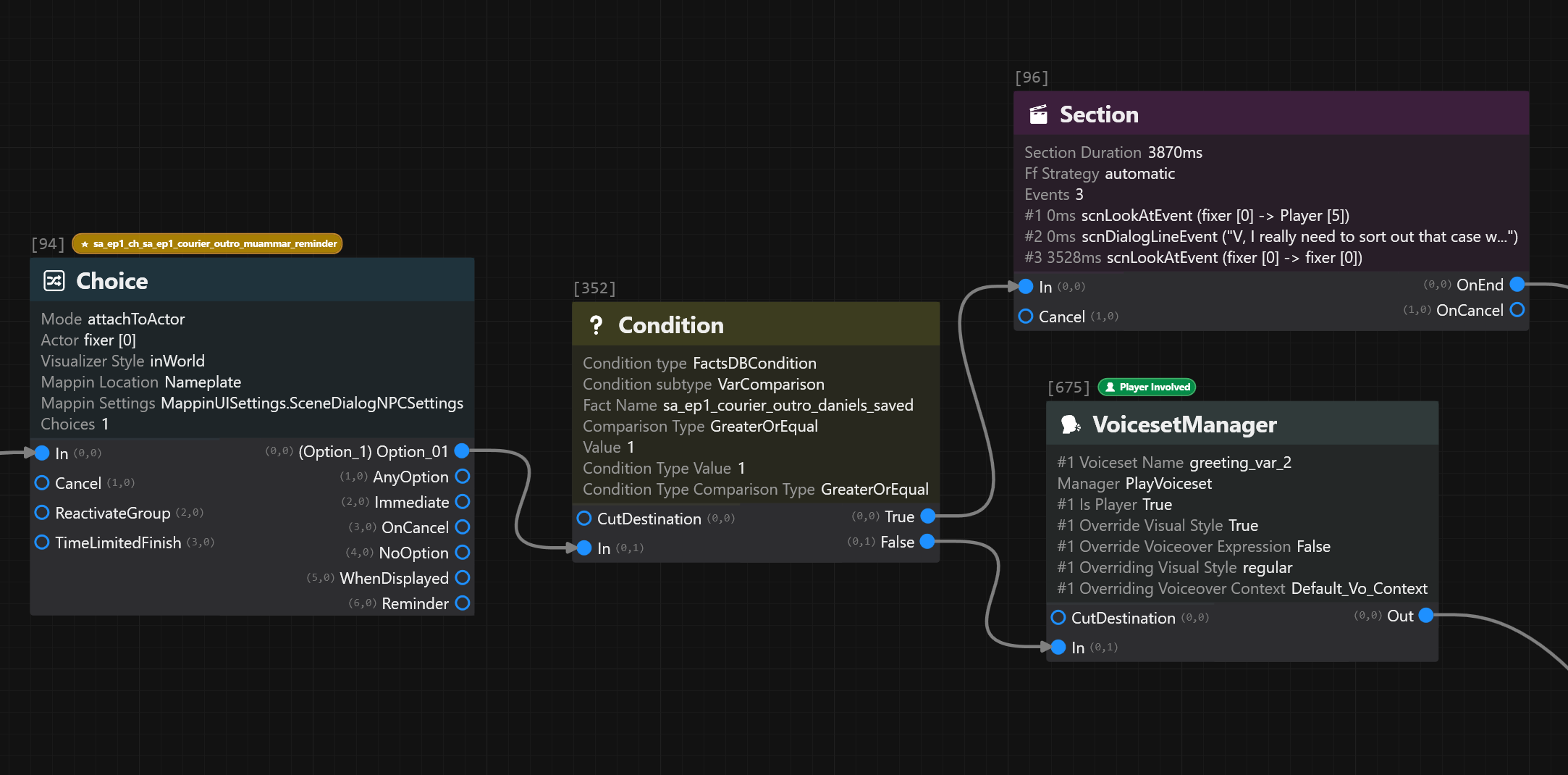

I loaded it up in Wolvenkit's quest editor. The graph view was functional - you could see nodes, connections, and edit properties by switching to the resource view. But working with it required a lot of context switching. The graph showed the flow, but to find details about a specific node or edit its properties, you'd jump to a deeply nested resource view. Properties showed ID numbers rather than readable names. Understanding a quest meant building a mental map across multiple disconnected views which isn't easy for a beginner.

I tried recreating mq049's structure for my own quest and it was slow going. Tasks like "make this NPC say this line" involved tracking ID numbers across views and carefully maintaining connections. The foundations were solid, but there was room to make the workflow more fluid.

The decision point

At this point, I had two choices: give up on my quest idea (again), or contribute to improving the tools. Wolvenkit is an incredible community project - it's what makes Cyberpunk modding possible at all. The maintainers had already built the foundation for quest editing and now there was an opportunity to take it to the next level.

That's where it started. I had previous C++ desktop app development experience but not as much with C# or .NET. I started learning while understanding the ins and outs of Wolvenkit's quest and scene views.

Understanding Cyberpunk's quest architecture

Before diving into the improvements, let me briefly explain how quests work in Cyberpunk. The game uses two main file types: .questphase and .scene files.

Questphases are the high-level orchestrators. They handle spawning NPCs, managing world states, updating journal entries, triggering rewards - the scaffolding of a quest. Think of them as the quest's logic and flow control.

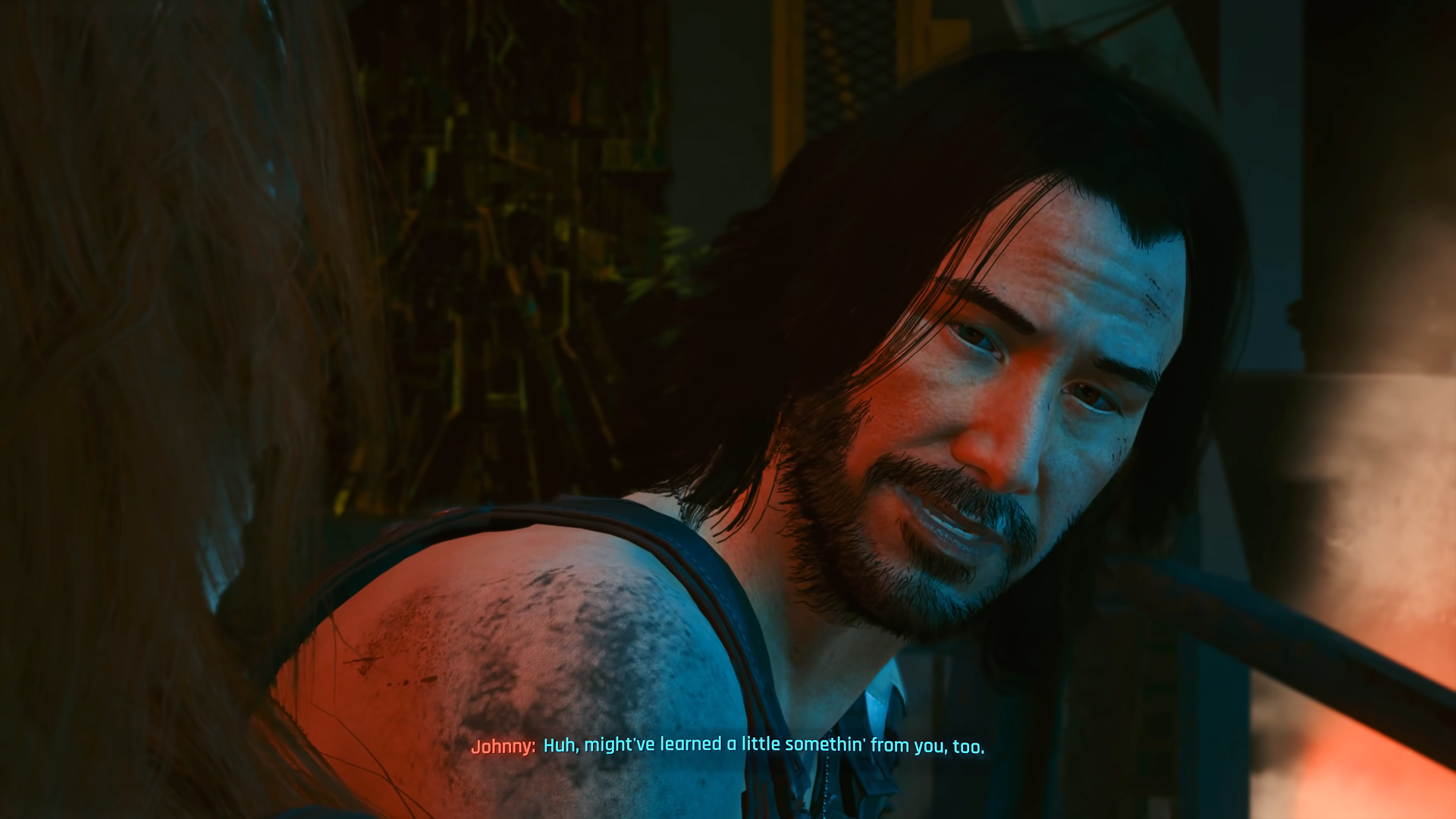

Scenes are where the storytelling happens. They control dialogue, animations, camera movements, the intimate character moments. When V and Johnny have a heart-to-heart on a rooftop, that's a scene file at work.

Note that most nodes in the quest system are technically "quest" nodes i.e. they inherit from questNodeDefinition- but you can have quest nodes in a scene - so a lot of the time, the boundary is blurry.

And other than that, both are represented as node graphs - visual flowcharts where each node is an action or decision, connected by lines showing the flow.

But here's where it gets interesting: scene files have MANY layers of metadata. Each node doesn't just say "play dialogue" - it specifies which actor, which animation set, which voice line, what the lighting should be, etc. This richness is what makes scenes feel cinematic, but it also makes them delicate to edit.

First steps: making nodes readable

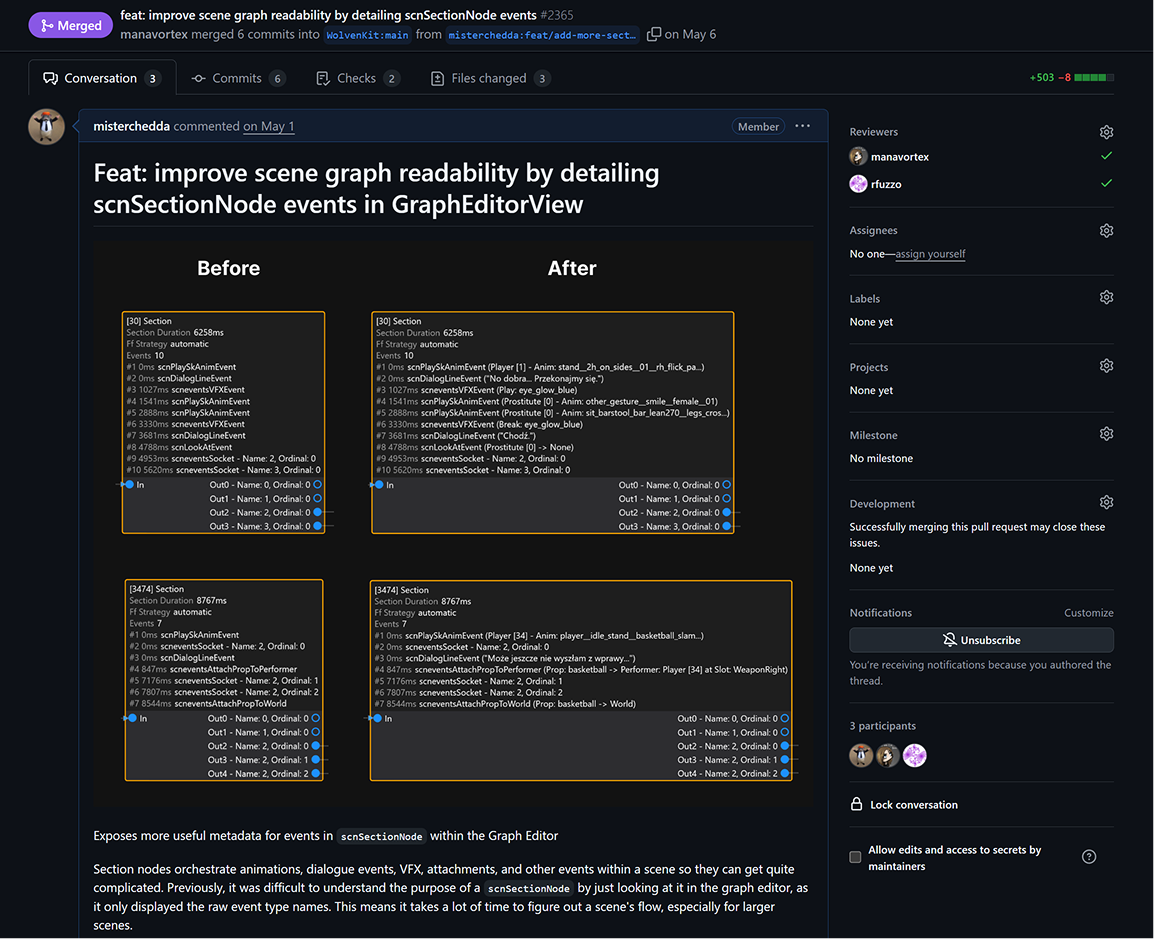

My first few PRs were focused on exposing more details directly in the scene graph view.

Section nodes are the heart of a scene. They orchestrate animations, dialogues, VFX/SFX, camera movements and more. They are containers that group related scene events together. But in the editor, they all looked identical - just boxes labeled "Section" and you had to click into each one to understand what it was doing.

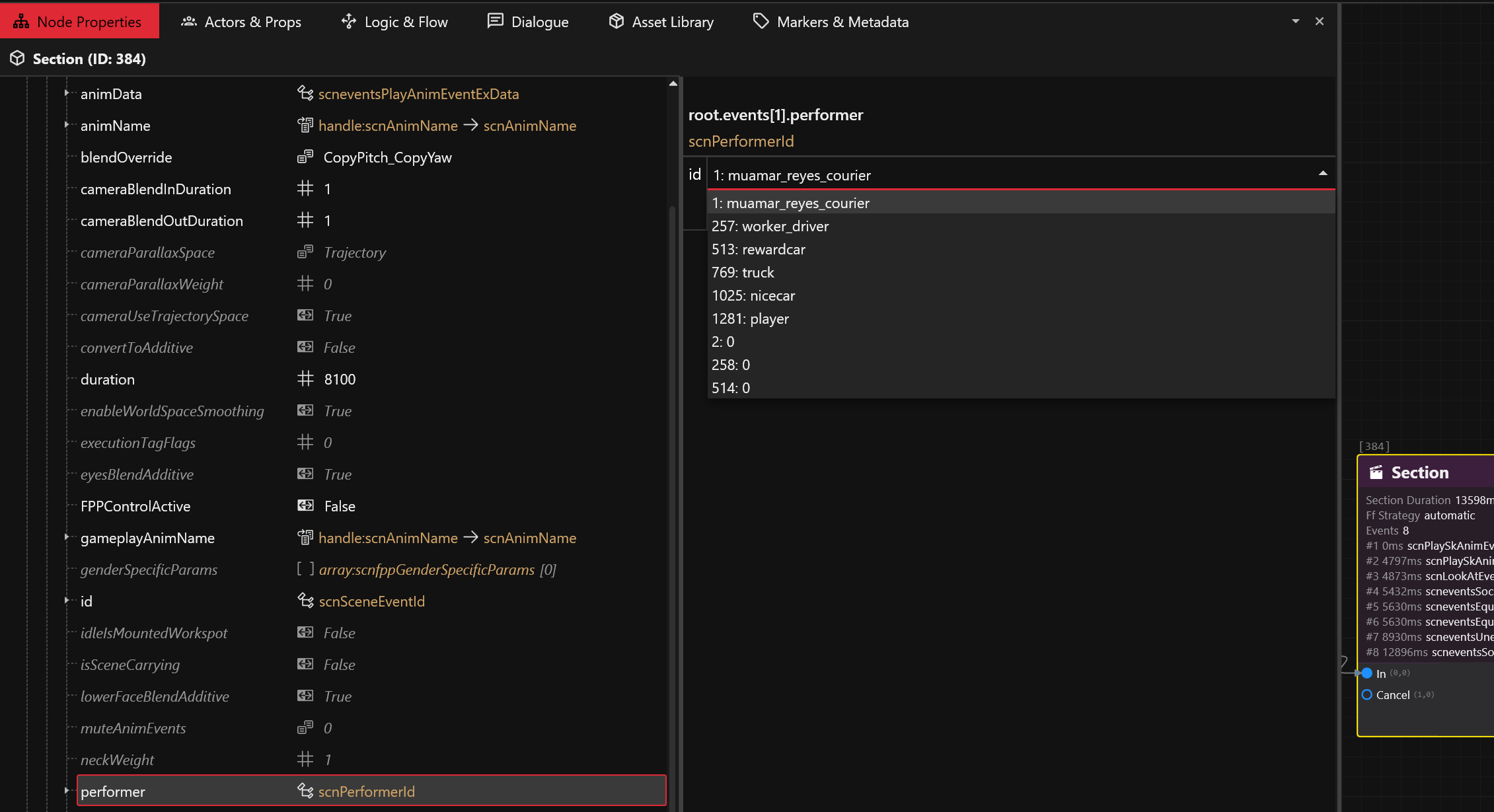

Next came the ID problem. Everything in scene files are referenced by IDs - actor 47, dialogue line 3892, animation set 15. For the game engine, that's efficient but for humans trying to create quests, it's a nightmare.

Naturally, the next step was to implement contextual dropdowns that translated these IDs into human-readable content. When you select an actor field, instead of typing "47", you see a dropdown with "Johnny Silverhand", "Viktor Vector", "Judy Alvarez". The editor queries the game's resource database and presents the actual content.

But it went deeper than just names. When selecting dialogue lines, you see the actual text. When choosing animations, you see descriptive names like "sit_casual_looking_around" instead of "a_set_15_idle_3" and so on.

A feature like this seems obvious in retrospect but it lets users unload a mental map of IDs and instead focus on the actual content.

The unification challenge

At this point, I realized the real problem wasn't any single issue - it was the fragmentation. You had a graph view for seeing flow, a resource view for editing properties, and a mind palace to connect them. Making a simple change required multiple window switches and careful attention to not lose your place. Miscalculated your dialog entry ID by a single number? That's 15 minutes of debugging why the game crashes.

The solution was rather clear this time: unify everything into a single, coherent interface. This meant essentially rebuilding the quest editor from its foundations. The graph and properties needed to exist in the same view, updating in real-time, speaking the same language. I knew this would be a big change, but after weeks of small improvements, I could see what needed to happen.

One thing that helped a lot in this process was looking at The Witcher 3's REDkit, which CDPR released a while back. It had a quest and scene editor that showed exactly how CDPR thinks about visual quest design. Cyberpunk's RED Engine 4 has WAY more node types (whereas TW3 has fewer node types which I suspect is because of the presence of script nodes in TW3 that do NOT exist in Cyberpunk - that let you write custom logic in code directly), but REDkit gave me a baseline. Small things like I noticed the editor used deletion markers when you delete a node - it becomes a placeholder instead of disappearing. It made sense once I thought about it because players have saves at different points in quests. If you hard-delete a Choice node or PauseCondition, anyone with a save at that node kinda gets stuck there forever. The deletion marker keeps the flow while removing the logic and looking at Cyberpunk's shipped quests, deletion markers were everywhere so quest designers used them constantly.

REDKit also confirmed a lot of things I suspected: one was that Section nodes are pivtol for scenes - REDKit has a whole timeline editor for it. And I'm betting Cyberpunk quest designers probably had an even more advanced timeliner editor as some of the Section nodes I've seen look like they're orchestrating entire subgraphs with over 100 events in a single node. It helped clue me in a lot about the complexity of not just the quest system but also how the UI and UX for the editor should feel like because the next big challenge was thinking about the design of the new unified editor.

For questphases - it's fairly simple: select a node and see its properties. But for scenes, I needed to organize all the properties in a way that made sense. I opted for a tabbed interface.

The unified view needed real-time sync between the graph and properties. Drag a connection in the graph, properties update instantly. Change a value in properties, the graph shows it. No more juggling mental models between different windows.

Cyberpunk's quest system is complex. You've got Phase nodes that encapsulate entire quest sections - basically mini-quests within quests. Scene nodes launch those .scene files we talked about. Switch nodes branch on game facts. Randomizer nodes for random outcomes. Each type has specific socket patterns and connection rules.

Phase nodes are particularly cool. They're containers holding entire subgraphs with internal logic, but they expose simplified sockets to the parent graph. The editor had to handle this nested complexity while keeping it understandable.

The visual language needed to be consistent too. I implemented a comprehensive color-coding system where each node type has its own color and icon. Quest nodes are blue, dialogue is green, logic gates are orange. But it goes beyond just colors - I added progressive path highlighting where the main story path renders with thicker lines while side branches use thinner strokes. You can now glance at a complex quest with hundreds of nodes and immediately understand its flow.

I also implemented a host of keyboard shortcuts and context menu actions that mirror professional tools. Ctrl+D to duplicate nodes (including all their properties but with fresh IDs and no connections). Arrow keys for spatial navigation between nodes using a "smart walk" system that considers both position and connection history. Ctrl+G to jump to any node by ID. Right-click menus that are context-aware - Randomizer nodes get "Add Output", Switch nodes get "Add Case" and so on.

During development, I wrote and ran over 15 "wscripts" (Wolvenkit's scripting framework) to understand CDPR's quest/scene patterns especially the socket patterns. One script analyzing scene files found something weird - scene nodes were missing their "CutDestination" input socket. Quest nodes had them, but scene nodes didn't. But here's the thing - the data showed 9,000 connections to these "missing" sockets across the game files. The connections were there all along, just not rendered in the editor. I later realized the community (notably Deceptious) had also noticed this but unfortunately it was never fixed.

The investigation turned up other interesting stuff too. There were these "1026,0" socket connections everywhere that made no sense at first. After programmatically digging through thousands of files, I figured out they were failsafes for the Cut Control system. When Cut Control triggers false, it connects to both the normal CutDestination and this backup socket. It's one of those engine quirks you only find by analyzing everything. Also a shoutout to Seberoth (a Wolvenkit maintainer) who chimed in and contributed to understanding the socket pattern distribution.

The PR that brought all this together touched 95 files, added 9,641 lines of code, and included 63 commits. It was the largest contribution I'd made to an open source project. The community was incredibly supportive throughout especially members like MrBill67 who provided a lot of hands on testing and feedback. I also documented what would be useful for modders in the Cyberpunk modding wiki including the socket patterns and documenting how quest/scene nodes work.

The Cyberpunk modding community is special - everyone genuinely wants to help each other create better content and I'm happy to have a chance to contribute back.